Textual hierarchy

The topmost linguistic level in the ETCBC analysis deals with textual hierarchy: decoding the linguistic cohesion of a written text. The point of departure is the assumption that a text is not just a linear arrangement of clauses, but that these clauses are arranged in a hierarchical structure, which can be described linguistically. Concretely, textual hierarchy involves the identification of connections between pairs of clauses, based on certain linguistic markers or patterns that indicate a syntactic and/or semantic interrelation between them. These interrelations can be of many different sorts, but broadly mean that the one clause “needs” the other for its proper interpretation in context.

Example

To illustrate this principle, consider the English translation of Jonah 1:3:

Text-hierarchic structure of Jonah 1:3.

Each clause is given a separate paragraph; the diagonal lines indicate the interrelations between them, where the lower clause in each pair (referred to as the daughter clause) “needs” the higher one (the mother clause) in order for it to be interpreted correctly. For example, to flee to Tarshish… is a daughter to But Jonah rose up, as it is a final clause that specifies rose up (shaded yellow). Similarly, which was going to Tarshish is a relative clause connected to a ship in the previous clause (shaded blue). So he went down to Joppa is connected to But Jonah rose up, since he went refers to Jonah (shaded green), while the same goes for found a ship, paid the fare, and and went down into it. None of the clauses in the example except the first would make much sense if found in isolation; that is, without their mother clauses to complete them syntactically and/or semantically. For example, found a ship occurring by itself would not only be “broken” syntactically for its lack of a subject, but also semantically, since it does not tell us who does the finding. To resolve these issues, a connection to a mother clause is needed to fill in the blanks. This may involve a multi-stage process, as is in fact the case in our example: First, found a ship is connected to So he went down to Joppa. While this clause is perfectly fine from a syntactic point of view (i.e., it could theoretically occur in isolation), it still remains semantically vague, as it does not tell us who the he is. A further connection, therefore, is made to But Jonah rose up.

Text-hierarchic trees

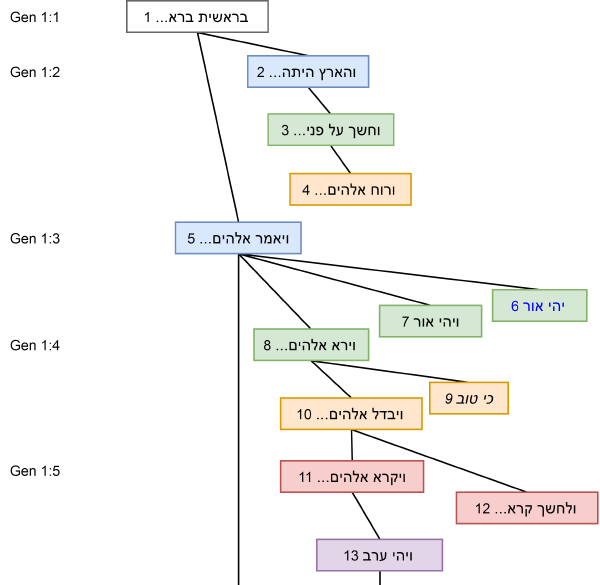

As the example for Jonah shows, the hierarchic structure of a textual passage takes the form of a tree, where clauses form the nodes, and the edges represent the various interrelations between them. A text-hierarchic tree will typically correspond to a coherent, self-contained passage of text; e.g., a narrative story, a poem, a prayer, etc. When a new passage begins, a new tree is initiated: either a completely new tree without any connection to previous ones, or, when the passage is framed within a larger passage, a subtree within a larger tree. For instance, a simplified visualization of the text-hierarchical structure of Genesis 1:1–10 might look as follows (click for large version):

Each clause forms a separate node in the tree (for each clause the opening words are given; numbers indicate the reading order; the shading indicates the “depth” of the clause in the tree counting from the top: white = level 1; blue = level 2, etc.). Vertical branches indicate so-called parallel interrelations, indicating a high degree of structural similarity between the clauses at hand, while non-vertical branches stand for dependent interrelations. Hebrew text printed in italics indicate constituent clauses (e.g., the object clauses 9 and 36 כי טוב, or the relative clauses 21 …אשר מתחת and 23 …אשר מעל), while blue text stands for direct speech (e.g. 6 יהי אור). The visualization provides us with an intuitive impression of the global structure of the narrative: A clear main line can be distinguished in the form of the vertical “backbone” across the center that strings together the opening clause …בראשית ברא with the subsequent stages in the Creation story, each of which is headed by a ויאמר אלהים clause that serves as the opening of its own subtree, where the details of each creation stage are laid out.

Tree size

In my research, I look at various properties of textual hierarchy trees. One of the phenomena that I am investigating is the relation between the size of a tree (i.e., of how many clauses it consists) and the linguistic properties of its opening clause. Since (sub)trees correspond to self-contained (sub)passages, the size of a particular tree may be said to reflect the “hierarchic dominance” of its opening clause: The more clauses which fall under the government of that opening clause, the larger a textual passage it is capable of tying together:

Tree size and predicate type

One of the features in the opening clause that appears to have a large correlation with the size of its tree is the predicate type (or “tense”) it uses. If we look at the different predicate types and compare them with the mean tree size falling under their domain, the following distribution is found for the Hebrew Bible (HB):

qtl = qatal; yqt = yiqtol; way = wayyiqtol; imp = imperfect; ptc = participle (active and passive); ifc = infinitive construct; ifa = infinitive absolute; nom = nominal predicate; ajv = adjectival predicate; w_p = without overt predicate.

Some interesting observations may be made in this preliminary survey. For instance, the highest mean tree size (21.746) is found when the opening clause of the tree contains a wayyiqtol. This neatly corresponds to what is well known about this verb form, namely that it is the proverbial tense used for structuring large narrative passages, both in opening them and stringing together in “wayyiqtol chains” corresponding to the subsequent stages or main turning points in the storyline.

Diachronic comparison between corpora

Since my research is part of the project Does Syntactic Variation Reflect Language Change? I focus on possible diachronic features that may be observed within the Hebrew Bible as well as the extra-Biblical corpora that are included in the project (several ancient Hebrew inscriptions, as well as selections from Qumran and Rabbinic Hebrew). To give an impression of the type of research that I have conducted, below is given a chart that indicates the mean tree size for opening clauses with a qatal predicate, compared across the different corpora, divided between main and subordinate clauses:

Ahi = Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions; Prex/Exil/Pstx = Hebrew Bible, “pre-exilic”, “exilic” and “post-exilic” portions (according to the consensus chronological model); Djd = Documents from the Judean Desert (i.e., Qumran Hebrew); Rh = Rabbinic Hebrew.

The x axis lists the six (sub)corpora under investigation; the lines indicate a proportional measure for mean tree size in each corpus (y axis on the left), while the bars correspond to the relative frequency of the predicate type at hand in each corpus (y axis on the right). Assuming that the corpora are presented in approximate diachronic order of composition (far from certain!), we might deduce from this chart that in main clauses (the blue line), there seems to be a gradual increase in the size of trees which open with a qatal clause, while in subordinate clauses (the orange line) no such trend is visible. The bars indicate that tree size is not simply a reflection of the relative frequency of qatal in these corpora. This observation may reflect at least two well-known processes: the gradual replacement in post-Biblical Hebrew of wayyiqtol by qatal, and the so-called penthouse principle which states that “more goes on upstairs than downstairs”; i.e., that main clauses show more variation and are more innovative than subordinate clauses, and thus tend to show new trends at an earlier stage in the evolution of the language. Similar comparisons have been conducted for the other predicate types. Whether the observed trends are truly reflected by the size of text-hierarchic trees remains to be established on the grounds of more statistically sound methods, which I hope to achieve in the near future.