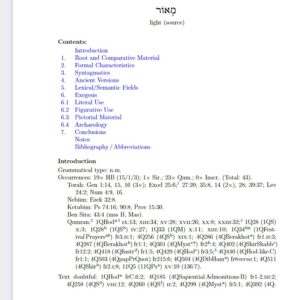

Sample of the first part of an entry in the SAHD database

The Semantics of Ancient Hebrew Database (SAHD) is a semantic thesaurus of classical Hebrew with the ambitious goal to collect and present as much relevant information as possible. This information includes a complete survey of the occurrences of the lemma in Biblical and other ancient Hebrew texts, their syntactical position, the semantic field, the early Bible translations, and the cognates in other Semitic languages.

The project was initiated some 35 years ago by Jacob Hoftijzer (1926-2011) and Karel Jongeling, who are well known from their publication of the Dictionary of North-West Semitic Inscriptions (published in 1995). In the introduction to that much praised dictionary they remark that they regret that they had to make many decisions about what to include and – much more difficult – what to leave out. They notice that the dictionaries on classical Hebrew were even more incomplete and lacked the specialised information about scholarly research used by the writer of the lemma for the chosen solution. For a number of lexemes, reference works like the Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, edited by Botterweck and Ringgren since 1970, filled in this gap, but this concerns only a limited collection of words. Would it not be great to have such a dictionary for all the lexemes of classical Hebrew? And would it not be great if it contained not only information about recent research but also the results of older research, and not only information reflecting the insights of the present author but also results with which he or she did not agree?

Hoftijzer and Jongeling realised that such a project asked more than the ten years both of them had worked on their dictionary on North-West Semitic inscriptions. International cooperation was necessary and also widely found. From the beginning they also realised that the collection and presentation of so many data required a clear concept of a semantic database, for which the then upcoming trend of digitalisation seemed to offer good opportunities. Hoftijzer formulates this very learnedly but also rather vaguely as “the construction of a kind of semantic meta-language/code system that gives the opportunity to incorporate several different semantic methods within the same framework.” For this reason “the collection of the relevant material in a database was preferable to a publication in book form.”

When we look at the output produced thus far, we get a picture that does not fully concur fully with the initial ideas. The website shows a list of entries referring to pdf files and to a number of monographs. In fact, it illustrates the two basic problems the project is facing: the lack of progress and the presentation of the data.

A new step was taken in 2017 with the cooperation with a related project of the Dutch and Flemish Old Testament Society (OTW) publishing on its website a series of articles with regard to lemma’s from the semantic field of utensils. Another step followed in 2019 with the cooperation with Reinier de Blois (United Bible Societies) and his project Semantic Dictionary of Biblical Hebrew (SDBH). Much work has been done since then to combine the websites. The online SAHD articles for example, have been integrated in their corresponding lexeme descriptions in SDBH through hyperlinks and updated definitions.

What is important now is that we motivate more scholars to participate in the work that still has to be done. The advantage of working together on this database is that there are many ways to contribute. It is teamwork; so you can contribute on the basis of your specific expertise and leave fields on which you do not feel at home (for instance, some of the Semitic languages or archaeology) to others. It is work in progress; so parts of the work on a lemma can already be published. It is also possible to involve students. There are already good experiences made with workshops on lexicography.

Hoftijzer and Jongeling would have been very happy with the possibilities we now have with regard to a multidimensional presentation of the material. When a new start was made through the cooperation of SAHD and the Dutch/Flemish utensils project, we realised that what is possible now is more than simply combining their two websites. An important step in the direction of a more sophisticated presentation is the cooperation with the website on the SDBH, which offers many ways to assess the data.

The second goal (next to the production of more entries) is to store all the information not in PDFs but on generated web pages and display them like Wikipedia pages. Semantic MediaWiki seems to be the right software to achieve this goal, not only because it helps to present the data is such a way that users can use the data in different ways, but also because it helps in the expansion production of the database. With Semantic MediaWiki simple forms can be set up for contributors to enter information and then that information can be manipulated to generate the final display page. A good example is the Old Testament Project of Tyndale House (I thank Elisabeth Robar of Cambridge Digital Bible Research for her information about this project and its method). Unfortunately, its website is still under construction, but via the list of websites using Semantic MediaWiki some examples from other fields can be given, for instance, the Aktanak project about stamp seals of the Middle East, or the German website Würzburger Datenbank sprachlicher Zweifelsfälle, or the Dutch website on hymns.

There is still a lot of work to do. Fortunately, we can cooperate with colleagues from Amsterdam, Cambridge, Oxford, Edinburgh, Leuven, Florence, and other academic centres. But we can certainly use more helping hands, both in lexicographical and in digital matters.