This second blogpost for the PaTraCoSy project brings us to a first discussion of the translation patterns from the Hebrew Bible into the Peshitta. Before we can address the results, we briefly describe how we constructed the model. After installation of Colibri Core, we follow the main thread in constructing the pattern modeling files, using the Colibri Core pattern modeller. These models can be found on our GitHub page, under respectively the directories Hebrew Source Files and Syriac Source Files. We do not need tokenization of the texts, because of our very specific choice of base text, provided by the ETCBC. Our first step then is class encoding the data of the two text files, resulting in .cls and .dat files.

Colibri-Core allows us to trace recurring patterns in a monolingual corpus, not allowing a direct comparison in a bilingual corpus. For this reason, we make two models, one for Hebrew, one for Syriac, while counting the amount of constructions, be they n-grams or skipgrams. At the moment, we do not yet use the flexgram functionality of Colibri Core, because we need the log-likelihood computation to interpret these results. This will be discussed in our next blogpost. We did not determine a maximum amount for the n-gram and skipgrams, only a base requirement of 10 attestations. This means that a word has to appear in at least 10 different constructions in order to be considered part of the model. We prefer indexed models, to be able to exactly trace back all patterns and their attestations within the corpus, although the memory requirements increase with this preference. We divided the corpus into newline segments for every new Bible verse, so the size of the skip gram will never exceed these boundaries, avoiding non-sensical combinations.

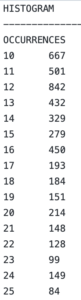

From the Colibri Core architecture, we can derive not only the type of data to be investigated, but also a succinct presentation in the form of reports and histograms.

The histogram (bar plot) of the entire biblical corpus for both languages, as shown numerically in these two pictures for the attestations between 10 and 25, can help us in detecting that Syriac (left) and Hebrew (right) have similar patterns, all within ten percent variance from each other. This histogram teaches us the values for each number of n-gram patterns. We can determine, for example, that in Hebrew 707 different constructions have exactly 10 occurrences, while in Syriac 667. These numbers do not provide much insight into the concerned patterns, but it allows us a general insight into the behavior of both texts. A similar file for the corresponding skipgram histogram is available on our GitHub. This also determines that, at least for this corpus, skipgrams too behave in a Zipfian fashion. This means that these structures follow the law of Zipf, a linguistic law stating that the frequency of a word is inversely proportional to its rank. This means that the second most attested word occurs half of the time of the most popular word, the third most attested one third of the time, …

The report for Hebrew and Syriac shows us more interesting information. For most types of structures, for example n-grams for n=3 or skipgrams with maximum of two skips, we find that Syriac has more patterns, and correspondingly a smaller coverage in the entire corpus. This pattern is near universal, leaving us to conclude that the Syriac translation is relatively flexible in that it provides several constructions corresponding to the Hebrew original. This overall trend can be applied to individual books, allowing us to deduce that Genesis has the widest variety of Syriac constructions compared to the Hebrew original, if we do not count poetic books, which are a separate category in dealing with translation patterns. This is another important reason to consider the book of Genesis as a first indicator of the types of translation patterns we can expect. In further research, we will be able to use these metrics to determine the typicality of certain translation patterns within the framework of the book in which they appear. This can be of great help to translation studies of ancient texts, since these patterns may reflect different authors, genres, and scribal schools.

Apart from this general insight, it is difficult to derive more insights into the translations as a whole, without looking at specific translation choices first, and their comparative place among other choices and patterns. A full description of these structures will allow us to discern general directions the translators took with respect to specific books, genres or semantic fields.

A first pattern we find is that where the translator chooses a word with a strongly different statistical distribution than its original. In general, the translator is not always consistent in his lexical choices, leading us to consider them term by term. In Genesis 2:6, for example, the Hebrew hapax legomenon (a word that occurs only once in the corpus) >D ‘mist(?)’ is translated by the more common Syriac word MBW<#> ‘source’. In this case, we cannot perform a comparative study of these terms, since there is only one single construction for Hebrew in which this term occurs. Sometimes, the Peshiṭta simply imports the Hebrew text into Syriac, leaving the often difficult to interpret or obscure meaning of the Hebrew undetermined. This in turn then produces hapax legomena in Syriac, leaving the interpretation fully to exegetes, who specialize in the interpretation of the original Hebrew text. In this sense, the Peshitta sometimes forsakes its task of being a true translation, placing loyalty to the original above ease of interpretation for the Syriac reader. When the translator imitates the Hebrew text, we are left guessing whether the translator understood the text in front of him.

A clear example of a specific translator choice being unloyal to the source text can be found in Genesis 2:2. The Hebrew BJWM HCBJ<J ‘on the seventh day’ is translated into the Syriac BJWM> CTJTJ> ‘on the sixth day’. The translation of numbers diverges only in this one single instance. This proves that this is a very exceptional situation, for theological reasons, rather than linguistic or cultural ones. On the other hand, the Hebrew BJWM occurs in 524 constructions, with a coverage 0.00171483, whereas in Syriac, this word occurs in 787 constructions with coverage 0.00249515. This allows us to conclude that Syriac uses the word for ‘day’ more freely than the Hebrew original.

A more specific example of the Syriac translation providing a concrete interpretation of the original can be found in Genesis 8:21. The Hebrew >T RJX HNJXX ‘the pleasing odor’ is translated into the Syriac RJX> DSWT> RJX> DNJX> ‘the sweet fragrance, the fragrance of repose’. In Hebrew, RJX occurs in 30 constructions with coverage 0,0000981775. In Syriac, it only occurs in 16 constructions, with coverage 0,0000507273. This overlap is very strong, with this example being the only example of a non-literal translation for this word. The opposite process can be found in Genesis 9:14, where the Hebrew WHJH B<NNJ <NN ‘when my clouding with clouds’ is rendered into a more straightforward Syriac DMSQ >N> <N”N> ‘when I bring up clouds’. We learn that in Hebrew, <NN occurs in 43 n-gram constructions with a coverage of 0.0001407211, whereas the Syriac <NN> occurs in 72, with a coverage of 0.000228273. Again, this is an example where the corresponding words in both language have nearly the same behaviour in n-gram/skipgram structure, except for a very specific case.

The final type of translation pattern is where a large variance between attested n-gram/skipgrams can be detected for semantically similar words, due to word play. A clear example can be found in Genesis 21:6. Here, the Hebrew YXQ… JYXQ LJ ‘laughter… let him laugh with me’ is translated into the Syriac XDWT>… NXD> LJ ’great joy… let him rejoice with me’. The Hebrew YXQ occurs in 82 constructions, with coverage 0.000268352, while the Syriac equivalent occurs 935 times, coverage 0.00296438. The Syriac translation occurs more than ten times as often as its Hebrew original. Investigating more closely why this divergence might be so elaborate, we conclude that the Hebrew verb refers through wordplay to Isaac, who appears in this context and whose name is near the same as the verb. Since this verb does not translate using the same lexeme in Syriac, this wordplay cannot be rendered in Syriac, leaving the translator no choice than to use another, far more common, word.